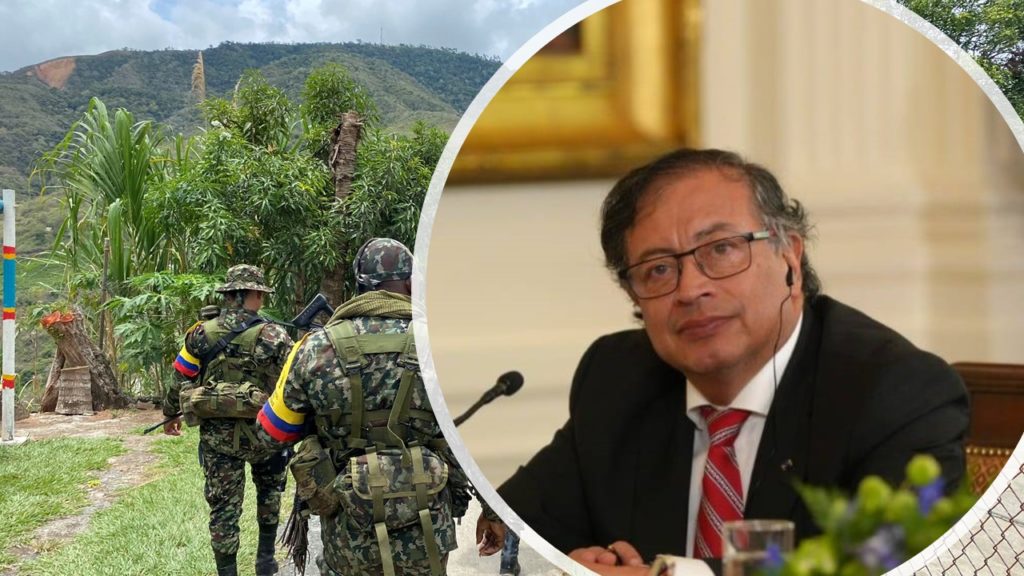

The road to peace has always been a difficult one to travel in Colombia. Total Peace, the project of President Gustavo Petro to end violence in Colombia, is going through its worst moment. Over the past weekend, two actions by the illegal armed organizations engaged in peace talks with the government have cast doubt on the peace efforts of the Colombian state.

Seven decades ago the last outbreak of violence began, and it continues to this day. Currently, the government of President Petro is advancing a project, called Total Peace, which aims once again to put an end to violence in Colombia. However, the facts demonstrate the enormous difficulties of this enterprise.

Today, the reality of the talks is confusing. With no significant advances, the ongoing crises in the talks with the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Central General Staff (EMC) survive in a state of permanent freeze. At the same time, the government is trying to approach paramilitary groups, such as the Gulf Clan, and another guerrilla group that was born as a dissident of the peace with the former FARC, in 2016: the Second Marquetalia, led by alias Ivan Marquez.

Systemic violence in Colombia

Unfortunately, violence in Colombia has been endemic. It dates back to the colonial era and the 19th century of incessant civil wars resulting from the failure to build an independent state through a social contract. In the 20th century, this practice continued until the last phase of the conflict began in the middle of the century.

The dictatorship of General Rojas Pinilla (1953-1957) ironically pacified the country. However, for the next 20 years, the pseudo-democratic regime that characterized national politics corrupted the democratic system to the point of completely discrediting it. The system in the 1960s and 1970s was simply an agreed-upon power-sharing arrangement between the two major parties, the Liberal and Conservative parties, which had been engaged in mutual hostilities for 100 years. This left other contenders unable to participate in electoral politics.

In this context, at a time when the Cuban Revolution (1959) seemed to offer a different way to attain power, a group of peasants took to the mountains armed with rudimentary weapons in response to a state which only showed them aggression. For a decade, they barely survived, relying on their knowledge of the rugged terrain of Colombian fields and jungles, with a romantic aura of popular resistance. Two organizations were born in 1964: the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN).

The cocaine boom in the 1970s transformed this handful of poorly dressed and poorly armed resisters into an irregular army with an increasingly potent killing capacity. Later, the logic of war, which justifies everything, gradually turned those guerrillas into fanatical criminals acting with increasing violence. Simultaneously, without them realizing it, they lost popular support, becoming entirely marginal in Colombian society, which associated the left with the violence and death caused by the guerrillas.

The long search for peace

Since the 1980s, every president has tried to make peace with the insurgencies, without success. Simultaneously, the stigmatization of progressive options, which experienced political genocide causing thousands of deaths in the 1980s and 1990s, continued. Paramilitary groups, often working in collusion with state entities, facilitated the assassination of trade unionists and left-wing politicians, leaving them with no opportunity to gain power through democratic means and bolstering the insurgents’ raison d’etre.

Of all the attempts to make peace, the most disastrous was led by conservative President Andres Pastrana (1998-2002). The demilitarization of a large zone in the heart of the country served to strengthen the FARC, which was at its zenith at that time. The spectacular failure of those negotiations gave a boost to former Senator Alvaro Uribe, who was barely known outside his hometown of Medellin at the time. Surprisingly, he won the 2002 elections, representing a tough stance against the insurgency.

This marked the beginning of eight years of relentless war against the FARC and other illegal armed groups. Despite the military offensive, these groups were not defeated. Politically, the FARC and the ELN had long ceased to exist.

Historic agreement with the FARC

When President Juan Manuel Santos took office in August 2010, everything seemed to be settled and secure. The former Defense Minister under President Uribe seemed to be continuing Uribe’s policy of a strong hand against armed insurgencies. However, Santos immediately signaled that he had his own agenda, independent of his political mentor. Two years later, in what appeared to be a personal vendetta aimed at derailing the peace process before it even began, Uribe publicly revealed on social media that Santos was secretly exploring negotiations with the formidable FARC-EP, the guerrilla group that had sown violence in Colombia’s countryside and cities for five decades. Santos had to publicly acknowledge Uribe’s claims.

The peace process began, and after four years of tough negotiations, with former Vice President Humberto de La Calle leading the government’s peace delegation, Colombia experienced a historic moment: the FARC laid down its arms and dissolved. Implementation of the agreements was marred by difficulties, and Santos’s successor, President Duque, had little interest in agreements he had denigrated two years earlier, which led to internal dissensions among the demobilized members.

Today, various armed groups, self-proclaimed dissidents of the 2016 peace agreement, have taken up arms and resumed the path of armed struggle. They are joined by existing bands, groups that are also dissidents of the paramilitary forces demobilized 20 years ago, and the long-standing and complex ELN, with whom Duque attempted peace, only to see the guerrillas blow it up after a criminal attack on a police academy in January 2019.

Total Peace, an ambitious and risky project

The historic 2022 election allowed a left-wing politician to come to power for the first time. Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla from the now-defunct M19, an organization very different from the FARC or ELN due to its urban nature, which demobilized in 1990, launched his Total Peace initiative. The idea was to build upon the significant progress made by President Santos. Petro extended an invitation to any illegal armed organization, regardless of ideology, to achieve widespread peace through dialogue. The first to accept the offer was the ELN, and recently, the most significant dissidence of the extinct FARC, the EMC, joined.

These two groups are quite different from the FARC. First, the ELN is federal, lacking a strong central power to effectively coordinate and decide, as was the case with the orthodox Marxist logic of the FARC. The media case of the kidnapping of Luis Manuel Diaz, father of the well-known Liverpool FC soccer player, a few months ago is a clear illustration of this. The peace delegates and the ELN central command were unaware that a unit of their organization in the north of the country was involved in the kidnapping. In other words, ELN units operate almost autonomously, which complicates peace negotiations and the achievement of an agreement that the whole group can support.

As for the EMC, it is a new and radicalized organization that has shown little or no maturity for dialogue with the state. However, a firm commitment to peace led the government to grant political status to a group that, beyond drug trafficking, has shown no significant political commitment. In November, President Petro acknowledged that dialogue with this organization “was perhaps premature”.

The future of Total Peace and the division in the guerrillas

In a session of political control, today, the High Commissioner for Peace, Otty Patiño, acknowledged the delicacy of the situation, while insisting on the importance of public efforts to continue on the road to peace. “We have six processes, including the one that will open soon with the Second Marquetalia; tables where the agreements are molded, but it is in the territories, with the people, that peace can be built,” Patiño said today before Colombia’s political representatives.

The State delegate for the peace office recognized that there is a part of the military structures of the EMC that “do not want peace”. That is why President Petro decided to break the ceasefire with this armed group in the south of the country, where these collectives are supposedly located, while the dialogue table with the EMC officially continues.

As for the ELN, Patiño regrets that its leadership “does not want to recognize that it is suffering an internal crisis”, where part of the organization is for peace and another part is not. Patiño assured that “the Comuneros front of the ELN and the Coordinadora Guerrillera del Pacifico de la Second Marquetalia have clearly shown their decision to join the dialogue proposed by the governor of that department, and they have done so not only with statements, but in the area of Abades we have begun a demining process.”.

On this line, the Commissioner for Peace affirmed that they will continue to dialogue with those who want peace, while military efforts will be redoubled to combat those who, with their actions, demonstrate that they continue to prefer the “path of war”.

The eternal scourge of drug trafficking

In Colombia, there is a significant catalyst for all political, social, and economic conflicts: drug trafficking. This practice, far from decreasing, has been increasing year after year. It is no longer large cartels, as in the 1980s, that dominate this illegal economy; instead, hundreds of small groups share a business that has made cocaine Colombia’s top export, surpassing oil.

However, the government of President Petro has already stated that the primary challenge to demobilizing these armed groups is the fight against the illicit economies that have made drug trafficking the core of their strategy and funding. The president criticized the lack of diligence in substituting these crops with sustainable, legal agriculture that could support a historically mistreated peasant population surviving on coca leaf cultivation.

To address this issue, the Colombian government has proposed new approaches to its allies abroad to redirect the fight against drug trafficking, citing the evident failure of existing approaches. The main challenge in this regard will be to persuade major cocaine consumers, the United States and Europe, to consider a different approach, including even the long-discussed idea of legalizing the substance. Similar changes were seen in the United States during President Roosevelt’s administration when Prohibition, a policy that had only served to empower criminal organizations and fuel violence in major cities, ended in 1933.

The President’s main challenge

Total Peace, along with the deep social reforms promised by the President, is currently the primary political battleground for President Petro. Success in normalizing the presence of left-wing parties in government will help illegal armed groups completely lose their political justification, which is now more theoretical than real, overshadowed by the drug trafficking practices that have eroded their political motivations.

The coming months will be crucial in determining whether Gustavo Petro can achieve his objectives. The challenge is immense, and enemies, both within and outside his government coalition, are waiting to pounce and discredit a bold and complex peace project in the eyes of public opinion.

The context is not favorable either. Colombia is a country where the ruling elite has grown accustomed to violence and the revenge of force. It’s worth noting that the nation voted “no to peace” in President Santos’s 2016 referendum on the agreement with the FARC. The success or failure of Total Peace will shape future presidencies and Colombia’s path toward a social pact model that has yet to be realized.

See all the latest news from Colombia and the world at ColombiaOne.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow Colombia One on Google News, Facebook, Instagram, and subscribe here to our newsletter.